Supreme Court Case Pollock v. Farmer's Loan and Trust Co. 1895

Background

The case was heard twice. In its first presentation, the issue was whether a tax upon rents or income issuing out of lands was constitutional, in the light of the clauses of the Constitution Article I, section 2, clause 3, and section 9, clause 4-which provide that "direct taxes" be apportioned among the states according to their population as established for representation in the House, and which prohibit any "cepitation, or other direct, tax" unless levied in proportion to the census enumeration. On the first hearing, the Court, by a vote of six to two, found that a tax on income from land, in order to be constitutional, must be apportioned according to population.

The case was heard twice. In its first presentation, the issue was whether a tax upon rents or income issuing out of lands was constitutional, in the light of the clauses of the Constitution Article I, section 2, clause 3, and section 9, clause 4-which provide that "direct taxes" be apportioned among the states according to their population as established for representation in the House, and which prohibit any "cepitation, or other direct, tax" unless levied in proportion to the census enumeration. On the first hearing, the Court, by a vote of six to two, found that a tax on income from land, in order to be constitutional, must be apportioned according to population.

The question remained whether a tax on other forms of income was also to fall under the Court`s ban. Justice Howell E. Jackson, who had been ill during the first argument of the case, returned. The entire Court, which had been divided four to four on important questions raised by this case, now heard a reargument. By a five to four vote, the Court decided that taxes on income from personal property were direct taxes, precisely as were taxes on income from land, and were therefore also unconstitutional. A roar of indignation went up throughout the country, though many conservatives were happy at what they considered a blow to "Populism." Because of this decision, the Sixteenth Amendment had to be passed in 1913 before income taxes could be levied.

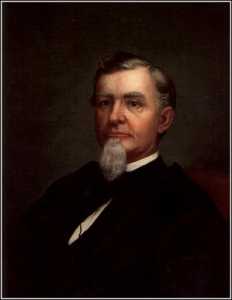

Mr. Chief Justice Fuller delivered the opinion of the court.

Our previous decision was confined to the consideration of the validity of the tax on the income from real estate, and on the income from municipal bonds. . .

Our previous decision was confined to the consideration of the validity of the tax on the income from real estate, and on the income from municipal bonds. . .

We are now permitted to broaden the field of inquiry, and to determine to which of the two great classes a tax upon a person's entire income, whether derived from rents, or products, or otherwise, of real estate, or from bonds, stocks, or other forms of personal property, belongs; and we are unable to conclude that the enforced subtraction from the yield of all the owner's real or per-sonal property, in the manner prescribed, is so different from a tax upon the property itself, that it is not a direct, but an indirect, tax in the meaning of the Constitution...

We know of no reason for holding otherwise than that the words "direct taxes," on the one hand, and "duties, imposts and excises," on the other, were used in the Constitution in their natural and obvious sense. Nor, in arriving at what those terms embrace, do we perceive any ground for enlarging them beyond, or narrowing them within, their natural and obvious import at the time the Constitution was framed and ratified. .

The reasons for the clauses of the Constitution in respect of direct taxation are not far to seek. .

The founders anticipated that the expenditures of the States, their counties, cities, and towns, would chiefly be met by direct taxation on accumulated property, while they expected that those of the Federal government would be for the most part met by indirect taxes. And in order that the power of direct taxation by the general government should not be exercised, except on necessity; and, when the necessity arose, should be so exercised as to leave the States at liberty to discharge their respective obligations, and should not be so exercised, unfairly and discriminatingly, as to particular States or otherwise, by a mere majority vote, possibly of those whose constituents were intentionally not subjected to any part of the burden, the qualified grant was made.

Those who made it knew that the power to tax involved the power to destroy, and that, in the language of Chief Justice Marshall, in McCulloch v. Maryland,

"the only security against the abuse of this power is found in the structure of the government itself.". . . And they retained this security by providing that direct taxation and representation in the lower house of Congress should be adjusted on the same measure.

Moreover, whatever the reasons for the constitutional provisions, there they are, and they appear to us to speak in plain language.

It is said that a tax on the whole income of property is not a direct tax in the meaning of the Constitution, but a duty, and, as a duty, leviable without apportionment, whether direct or indirect. We do not think so. Direct taxation was not restricted in one breath, and the restriction blown to the winds in another.

The Constitution prohibits any direct tax, unless in proportion to numbers as ascertained by the census; and, in the light of the circumstances to which we have referred, is it not an evasion of that prohibition to hold that a general unapportioned tax, imposed upon all property owners as a body for or in respect of their property, is not direct, in the meaning of the Constitution, because confined to the income therefrom?

Whatever the speculative views of political economists or revenue reformers may be, can it be properly held that the Constitution, taken in its plain and obvious sense, and with due regard to the circumstances attending the formation of the government, authorizes a general unapportioned tax on the products of the farm and the rents of real estate, although imposed merely because of ownership and with no possible means of escape from payment, as belonging to a totally different class from that which includes the property from whence the income proceeds?

There can be but one answer, unless the constitutional restriction is to be treated as utterly illusory and futile, and the object of its framers defeated. We find it impossible to hold that a fundamental requisition, deemed so important as to be enforced by two provisions, one affirmative and one negative, can be refined away by forced distinctions between that which gives value to property, and the property itsell.

Nor can we perceive any ground why the same reasoning does not apply to capital in personalty held for the purpose of income or ordinarily yielding income, and to the income therefrom. . .

Personal property of some kind is of general distribution; and so are incomes, though the taxable range thereof might be narrowed through large exemptions. . .

Nor are we impressed with the contention that, because in the four instances in which the power of direct taxation has been exercised, Congress did not see fit, for reasons of expediency, to levy a tax upon personalty, this amounts to such a practical construction of the Constitution that the power did not exist, that we must regard ourselves bound by it. We should regret to be compelled to hold the powers of the general government thus restricted, and certainly cannot accede to the idea that the Constitution has become weakened by a particular course of in-action under it. .

Admitting that this act taxes the income of property irrespective of its source, still we cannot doubt that such a tax Is necessarily a direct tax in the meaning of the Constitution.

The power to tax real and personal property and the income from both, there being an apportionment, is conceded; that such a tax is a direct tax in the meaning of the Constitution has not been, and, in our judgment, cannot be successfully denied; and yet we are thus invited to hesitate in the enforcement of the mandate of the Constitution, which prohibits Congress from laying a direct tax on the revenue from property of the citizen without regard to state lines, and in such manner that the States cannot intervene by payment in regulation of their oWn resources, lest a government of delegated powers should be found to be, not less powerful, but less absolute, than the imagination of the advocate had supposed.

We are not here concerned with the question whether an income tax be or be not desirable, nor whether such a tax would enable the government to diminish taxes on consumption and duties on imports, and to enter upon what may be believed to be a reform of its fiscal and commercial system. Questions of that character belong to the controversies of political parties, and cannot be settled by judicial decision. In these cases our province is to determine whether this income tax on the revenue from property does or does not belong to the class of direct taxes. If it does, it is, being unapportioned, in violation of the Constitution, and we must so declare. . .

Our conclusions may, therefore, he summed up as follows:

- First.

- We adhere to the opinion already announced, that, taxes on real estate being indisputably direct taxes, taxes on the rents or income of real estate are equally direct taxes.

- Second.

- We are of opinion that taxes on personal property, or on the income of personal property, are likewise direct taxes.

- Third.

- The tax imposed by sections twenty-seven to thirty-seven, inclusive, of the act of 1894, so far as it falls on the income of real estate and of personal property, being a direct tax within the meaning of the Constitution, and, therefore, unconstitutional and void because not apportioned according to representation, all those sections, constituting one entire scheme of taxation, are necessarily invalid.

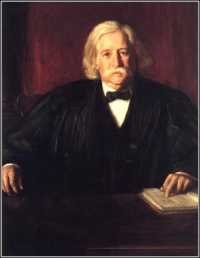

Excerpt from: John Marshall Harlan, Dissenting Opinion

Justice Harlan, along with three of his brethren, dissented ftom the decision in the Pollock case. The New York Sun, reporting the event, said that in delivering his dissent, Justice Harlan "pounded the desk, shook his finger under the noses of the Chief Justice and Mr. Justice Field, turned more than once almost angrily upon his colleagues in the majority, and expressed his dissent from their conclusions in a tone and language more appropriate to a stump address at a Populist barbecue then to an opinion on a question of law before the Supreme Court of the United States." Whatever Harlan`s manner, his dissent, of which only a small part appears here, was a long and learned discussion of the historical and legal issues raised by the "direct tax" question. Not only the Court`s precedents, but the records of the Federal Convention of 1787 bore out his arguments. For the direct tax clauses had been intended to apply only to the taxation of land and of persons, having been passed to meet the demands of Southerners in the Convention who were concerned lest their land be taxed by its area and their slaves be taxed by their numbers. In the Hylton case of 1796 (to which Justice Harlan refers), the Court, two of whose Justices had been members of the Convention and had actually taken part in the writing of the direct tax clause, had passed clearly upon its historic meaning. Subsequent historians of the Court have generally agreed with the argument of this heated dissent, and a later Chief Justice, Chales Evans Hughes, once referred to the majority decision in the case as a self-inflicted wound.

Justice Harlan, along with three of his brethren, dissented ftom the decision in the Pollock case. The New York Sun, reporting the event, said that in delivering his dissent, Justice Harlan "pounded the desk, shook his finger under the noses of the Chief Justice and Mr. Justice Field, turned more than once almost angrily upon his colleagues in the majority, and expressed his dissent from their conclusions in a tone and language more appropriate to a stump address at a Populist barbecue then to an opinion on a question of law before the Supreme Court of the United States." Whatever Harlan`s manner, his dissent, of which only a small part appears here, was a long and learned discussion of the historical and legal issues raised by the "direct tax" question. Not only the Court`s precedents, but the records of the Federal Convention of 1787 bore out his arguments. For the direct tax clauses had been intended to apply only to the taxation of land and of persons, having been passed to meet the demands of Southerners in the Convention who were concerned lest their land be taxed by its area and their slaves be taxed by their numbers. In the Hylton case of 1796 (to which Justice Harlan refers), the Court, two of whose Justices had been members of the Convention and had actually taken part in the writing of the direct tax clause, had passed clearly upon its historic meaning. Subsequent historians of the Court have generally agreed with the argument of this heated dissent, and a later Chief Justice, Chales Evans Hughes, once referred to the majority decision in the case as a self-inflicted wound. Let us examine the grounds upon which the decision of the majority rests, and look at some of the consequences that may result from the principles now announced. I have a deep, abiding conviction, which my sense of duty compels me to express, that it is not possible for this court to have rendered any judgment more to be regretted than the one

just rendered....

Let us examine the grounds upon which the decision of the majority rests, and look at some of the consequences that may result from the principles now announced. I have a deep, abiding conviction, which my sense of duty compels me to express, that it is not possible for this court to have rendered any judgment more to be regretted than the one

just rendered....

In my judgment a tax on income derived from real property ought not to be, and until now has never been, regarded by any court as a direct tax on such property within the meaning of the Constitution. As the great mass of lands in most of the States do not bring any rents, and as incomes from rents vary in the different States, such a tax cannot possibly be apportioned among the States on the basis merely of numbers with any approach to equality of right among taxpayers, any more than a tax on carriages or other personal property could be so apportioned. And, in view of former adjudications, beginning with the Hylton case and ending with the Springer case, a decision now that a tax on income from real property can be laid and collected only by apportioning the same among the States, on the basis of numbers, may, not improperly, be regarded as a judicial revolution, that may sow the seeds of hate and distrust among the people of different sections of our common country. . .

But the court, by its judgment just rendered, goes far in advance not only of its former decisions, but of any decision heretofore rendered by an American court.

In my judgment-to say nothing of the disregard of the former adjudications of this court, and of the settled practice of the government-this decision may well excite the gravest apprehensions. It strikes at the very foundations of national authority, in that it denies to the general government a power which is, or may become, vital to the very existence and preservation of the Union in a national emergency, such as that of war With a great commercial nation, during which the collection of all duties upon imports will cease or be materially diminished. It tends to ree'stablish that condition of helplessness in which Congress found itself during the period of the Articles of Confederation, when it was without authority, by laws operating directly upon individuals, to lay and collect, through its own agents, taxes sufficient to pay the debts and defray the expenses of government, but was dependent, in all such matters, upon the good will of the States, and their promptness in meeting requisitions made upon them by Congress.

Why do I say that the decision just rendered impairs or menaces the national authority? The reason is so apparent that it need only be stated. In its practical operation this decision withdraws from national taxation not only all incomes derived from real estate, but tangible personal property, "invested personal property, bonds, stocks, investments of all kinds," and the income that may be derived from such property. This results from the fact that by the decision of the court, all such personal property and all incomes from real estate and personal property, are placed beyond national taxation otherwise than by apportionment among the States on the basis simply of population. No such apportionment can possibly be made without doing gross injustice to the many for the benefit of the favored few in particular States. Any attempt upon the part of Congress to apportion among the States, upon the basis simply of their population, taxation of personal property or of incomes, would tend to arouse such indignation among the freemen of America that it would never be repeated. . .

The decree now passed dislocates-principally, for reasons of an economic nature-a sovereign power expressly granted to the general government and long recognized and fully established by judicial decisions and legislative actions. It so interprets constitutional provisions, originally designed to protect the slave property against oppressive taxation, as to give privileges and immunities never contemplated by the founders of the government.

I cannot assent to an interpretation of the Constitution that impairs and cripples the just powers of the National Government in the essential matter of taxation, and at the same time discriminates against the greater part of the people of our country.

The practical effect of the decision to-day is to give to certain kinds of property a position of favoritism and advantage inconsistent with the fundamental principles of our social organization, and to invest them with power and influence that may be perilous to that portion of the American people upon whom rests the larger part of the burdens of the government, and who ought not to be subjected to the dominion of aggregated wealth any more than the property of the country should be at the mercy of the lawless.