Introduction

"You may not believe me, but things was just that

way,

Black is nothing other than a darker shade of rebel

gray."

The Rebelaires (1)

When Shirley Temple, in the movie The Littlest Rebel (1933) is play-training her slaves into a company of colored soldiers, she defies the Yankee ways by inverting the commands for "halt" and "march." In a way, she also defies a nation's historiography and its reflection in movies. Examples of Civil War movies in which colored soldiers are fighting for the Union are abundant; not counting the faux-company of little Temple, Confederate blacks have to make do with non-military characters in the indie-film Pharaoh's Army (1995) and Ride with the Devil (1999).

Not only popular culture, but also much of historical

writing is characterized by a lack of Black Confederates.

When Civil War scholar James McPherson, in his The Negro's

Civil War, lists a great number of books about the role of

blacks in the Civil War, they all deal with the position of

blacks as slaves or their struggle in Northern armies.(2)

Those books were written before 1965, but the same goes for

most books written afterwards. A typical work is Slavery

Remembered of historian Elcott, who explicitly states that

"almost two hundred thousand blacks [...] fought on the

Union side" and thus "made an indispensible contribution to

victory," but never mentions the possibility of slaves

serving the Confederacy.(3)

Not only popular culture, but also much of historical

writing is characterized by a lack of Black Confederates.

When Civil War scholar James McPherson, in his The Negro's

Civil War, lists a great number of books about the role of

blacks in the Civil War, they all deal with the position of

blacks as slaves or their struggle in Northern armies.(2)

Those books were written before 1965, but the same goes for

most books written afterwards. A typical work is Slavery

Remembered of historian Elcott, who explicitly states that

"almost two hundred thousand blacks [...] fought on the

Union side" and thus "made an indispensible contribution to

victory," but never mentions the possibility of slaves

serving the Confederacy.(3)

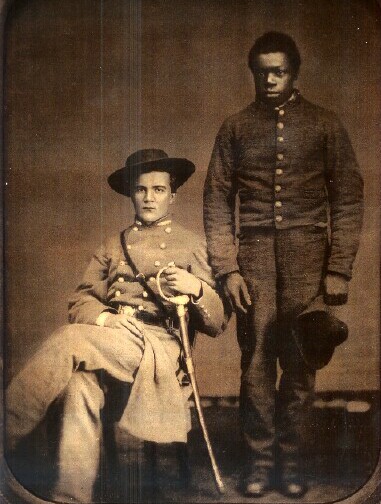

In 1989 there was a turning point in historiography: that year featured the film Glory, which centered around an all-black Union regiment that fought bravely for freedom. This prominence led to a nation-wide recognition of courageous blacks fighting for the North. In addition, it sparked among some scholars the notion that another group was being left out that deserved to be honored: namely, blacks who fought for the South.(4) Among these scholars are Richard Rollins, vice-president of a software company and editor; Ervin L. Jordan, associate curator at the University of Virginia library; Charles Kelly Barrow, a social studies teacher and chief historian of Sons of the Confederate Veterans; and J.H. Segars, who holds a degree in education. Most notable in the revival of the notion that there were many black Confederates, is that these authors have systematically compiled scattered sources to base their assumptions on-and thus try to build significance.

The main use of "black Confederates" in this essay is in referce to black soldiers, or blacks fighting in the armed forces. Whereas most historians agree that there were cooks, seamsters, and servants, the center of the debate is on whether a substantial number of blacks took up arms and actively fought for the South. This becomes obvious when one considers that the number proposed by proponents lies at roughly 30,000 fighting men, while Civil War historians such as McPherson and Glatthaar put the number much lower: at at most a few hundred.(5)

The focal point of this essay lies in the clarification of the large discrepancy between the numbers of black soldiers, as interpreted by the different historians of both sides of the debate, and in answering the question whether there was a significant number of black Confederate soldiers, deserving the attention of a larger body of historians.