The split grows deeper

Then Stephen A. Douglas, senior Senator from Illinois, cut through the opposition in 1854 by proposing a bill that enraged all free-soil men. Douglas argued that since the Compromise of 1850 left Utah and New Mexico free to decide on slavery for themselves, the Missouri Compromise had been long since superseded. His plan projected the organization of two territories, Kansas and Nebraska, and permitted settlers to carry slaves into them. The inhabitants themselves were to determine whether they should enter the Union as free or slave states. Northerners accused Douglas of currying favor with the south in order to gain the presidency in 1856. Indeed, his political ambitions were unquestionably strong. But if he believed that northern sentiment would tamely accept his plan, he was quickly undeceived. To open these rich western prairies to slavery struck millions of men as unforgivable. Angry debates marked the progress of the bill. The free-soil press violently denounced it. Northern clergymen assailed it from thousands of pulpits. Businessmen who had hitherto befriended the south turned suddenly aboutface. Yet, on a May morning, the bill passed the Senate amid the boom of cannon fired by southern enthusiasts. At the time, Salmon P. Chase, an antislavery leader, prophesied: "They celebrate a present victory, but the echoes they awaken shall never rest until slavery itself shall die." When Douglas subsequently visited Chicago to speak in his own defense, the ships in the harbor lowered their flags to half-mast, the church bells tolled for an hour, and a crowd of ten thousand hooted so that he could not make himself heard.

The immediate results of Douglas' ill-starred measure were momentous. The Whig party, which had straddled the question of slavery expansion, sank to its death, and in its stead arose a powerful new organization, the Republican Party, Its primary demand was that slavery be excluded from all the territories. In 1856, it nominated for the presidency the dashing John Fr6mont, whose five exploring expeditions into the far west had won him deserved renown. Although it lost the election, the new party swept a great part of the north. Such free-soil leaders as Chase and William Seward rose to greater influence than ever. Along with them appeared a tall, gaunt Illinois attorney, Abraham Lincoln, who showed marvelous logic in discussing the new issues. The flow of southern slaveholders and northern antislavery men into Kansas produced grim antagonism. Before long, as a result of sharp armed conflicts, the territory was called "bleeding Kansas."

"Every nation that carries in its bosom great and unredressed injustice," Mrs. Stowe had written, "faces the possibility of an awful convulsion." As the years passed, events brought the nation closer to the inevitable upheaval. In 1857, the Supreme Court's famous decision concerning Dred Scott was announced. Scott was a Missouri slave who some twenty years before had been taken by his master to reside in Illinois and Wisconsin territory where slavery was forbidden. Returning to Missouri and becoming discontented with his lot, Scott began suit for liberation on the ground of his residence on free soil. The southern-dominated court decided that by voluntarily returning to a slave state, Scott had lost whatever title he possessed to liberty and ruled, furthermore, that any attempt of Congress to prohibit slavery in the territories was invalid.

|

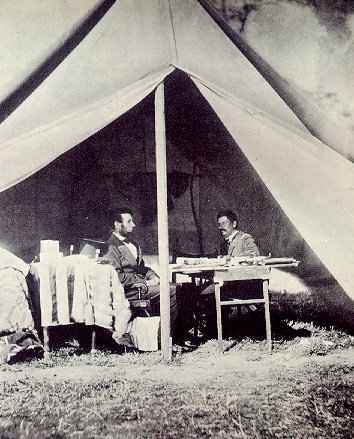

| Soon after the crucial battle of Antietam, Linoln visited the Union general, McCellan, at his field headquarters for a conference on the war's progress. |