The Dutch left their influences

The Dutch possessed New Netherland, later to be called New York, for forty years. But they were not a migrating people. There was land and to spare in Holland, and colonizing offered them neither political nor religious advantages which they did not already enjoy. In addition, the Dutch West India Company, which undertook to establish the new world settlement, found it difficult to find competent officials to keep, the colony running smoothly. Then in 1664, with a revival of British interest in colonial activity, the Dutch settlement was taken over through conquest. Long after this, however, the Dutch continued to exercise an important social and economic influence. Their sharp-stepped gabled roofs became a permanent part of the landscape, and their merchants gave the city its characteristic commercial atmosphere.

The habits bequeathed by the Dutch also gave New York a hospitality to the pleasures of everyday life quite different from the

austere atmosphere of Puritan Boston. In New York, holidays were marked by feasting and merrymaking. And many Dutch

customs-like the habit of calling on one's neighbors and sharing a drink with them on New Year's Day and the visit of jovial Saint

Nicholas at Christmas time-became countrywide customs which have survived to the present day.

The habits bequeathed by the Dutch also gave New York a hospitality to the pleasures of everyday life quite different from the

austere atmosphere of Puritan Boston. In New York, holidays were marked by feasting and merrymaking. And many Dutch

customs-like the habit of calling on one's neighbors and sharing a drink with them on New Year's Day and the visit of jovial Saint

Nicholas at Christmas time-became countrywide customs which have survived to the present day.

With the transfer from Dutch authority, an English administrator set about remodeling the legal structure of New York to fit English traditions. He did his work so gradually and with such wisdom and tact that he won the friendship and respect of Dutch and English alike. Town governments had the autonomy characteristics of New England towns and in a few years there was a reasonably workable fusion between residual Dutch law and customs and English procedures and practice.

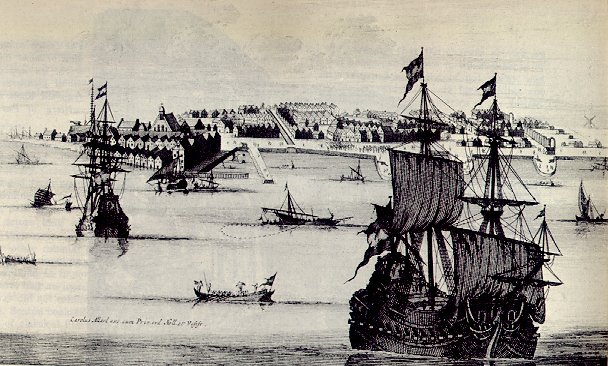

By 1696, nearly 30,000 people lived in the province of New York. In the rich valleys of the Hudson, Mohawk, and other rivers,

great estates flourished, and tenant farmers and small freehold farmers contributed to the agricultural development of the region.

For most of the year, the grasslands and woods supplied feed for cattle, sheep, horses, and pigs; tobacco and flax grew with ease,

and fruits, especially apples, were abundant. But great as was the value of farm products, the fur trade also contributed to the

growth of New York and Albany as cities of consequence. For from Albany, the Hudson River was a convenient waterway for

shipping furs and northern farm products to the busy port of New York.

In direct contrast to New England and the middle colonies was the predominantly rural character of the southern settlements of Virginia, Maryland, the Carolinas, and Georgia. Jamestown, in Virginia, was the first colony to survive in the new world. Late in December 1606, a motley group of about a hundred men, sponsored by a London colonizing company, set out in search of a great adventure. They dreamed of quick riches from gold and precious stones. Homes in the wilderness were not their goal. Among them, Captain John Smith emerged as the dominant spirit, and despite quarrels, starvation, and the constant threat of Indian attacks, his will held the little colony together through the first years. In the earliest days, the promoting company, ever eager for quick returns, required the colonists to concentrate on producing for export naval stores, lumber, roots, and other products for sale in the London market, instead of permitting them to plant crops and otherwise provide for their own subsistence. After a few disastrous years, however, the company eased its requirements, distributed land to the colonists, and allowed them to devote most of their energies to private undertakings. Then, in 1612, a development occurred which ultimately revolutionized the economy, not only of Virginia, but of the whole contiguous region. This was the discovery of a method of curing Virginia tobacco which would make it palatable to European tastes. The first shipment of this tobacco reached London in 1614, and within a decade the plant gave every promise of becoming a steady and profitable source of revenue.