Farmers face hardships

Yet despite these advances, the American farmer in the nineteenth century was subject to recurring periods of critical hardship. Indeed, at the close of the century of greatest agricultural expansion, the dilemma of the farmer had become a major problem. Several basic factors were involved-soil exhaustion, the vagaries of nature, overproduction of staple crops, decline in self-sufficiency, and lack of adequate legislative protection and aid. Southern soil had long been exhausted by tobacco and cotton culture, but in the west, and on the plains too, soil erosion, wind storms, and insect pests ravaged the land.

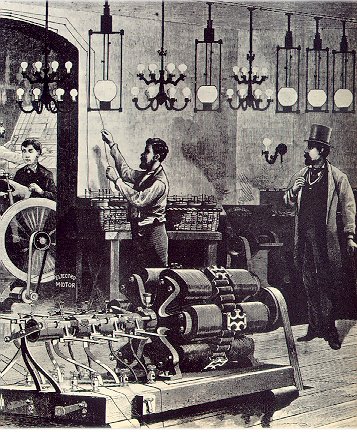

The swift mechanization of agriculture west of the Mississippi had not proved an unmixed blessing. It encouraged many farmers to expand their holdings unwisely; it stimulated concentration on staple crops; it gave large farmers a distinct advantage over small ones and hastened, at once, the development of tenancy and of farming on an extremely large scale. These problems were to remain largely unsolved until the widespread acceptance of modern soil conservation techniques many years later.

Even more complex, but more readily susceptible to swift remedial action, was the problem of prices. The farmer sold his

product in a competitive world market but purchased his supplies, equipment, and household goods in a market protected

against competition. The price he got for his wheat and cotton or beef was determined abroad; the price he paid for his

harvester, his fertilizer, his barbed wire was fixed by trusts setting prices behind a protective tariff. From 1870 to 1890 prices of

most farm products moved irregularly downward, and the value of American farm products increased only half a billion dollars.

In the same period, however, the value of manufactures increased by six billion dollars.

Even more complex, but more readily susceptible to swift remedial action, was the problem of prices. The farmer sold his

product in a competitive world market but purchased his supplies, equipment, and household goods in a market protected

against competition. The price he got for his wheat and cotton or beef was determined abroad; the price he paid for his

harvester, his fertilizer, his barbed wire was fixed by trusts setting prices behind a protective tariff. From 1870 to 1890 prices of

most farm products moved irregularly downward, and the value of American farm products increased only half a billion dollars.

In the same period, however, the value of manufactures increased by six billion dollars.

This economic unbalance led to the formation of farmers' organizations to consider common grievances and propose means of relief. Most of these were patterned after the Grange established in 1867. Within a few years, there were Granges in almost every state, and membership exceeded three-quarters of a million. These groups began chiefly as social organizations designed to lessen the farmer's isolation. Inevitably, however, their members turned to discussions of business and politics. Talk led to action, and soon many of the Granges set up cooperative marketing organizations, cooperative stores, and even factories. In a number of midwestern states, they elected members to the legislature and passed laws regulating railroads and warehouses. Many of the Grange business enterprises failed, however, and at the same time, the farms enjoyed a resurgence of prosperity in the late seventies. In consequence, the Grange dwindled in importance. The movement it had started, however, revived in the Farmers' Alliances which began in the late eighties and early nineties. Times were once more hard; drought had descended on the stricken plains; the price of wheat and cotton plunged. Thus stimulated, the Alliance movement spread quickly and by 1890 it had nearly two million members. In addition to an extensive educational program, these groups made active demands for political reform. Before long, the Alliances were metamorphosed into a crusading political party. Known as the Populists, they vigorously opposed the old Democratic and Republican parties.