U.S. Opposes Europe's Threats

When the Alliance turned its attention to Spain and her colonies in the New World, it severely shook the confidence of the United States in the permanence of the new South American governments. To the United States Government, which for years had practiced the policy of aloofness laid down by Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson, John Adams, and others, this appeared to be a flagrant attempt on the part of European powers to occupy the territories that had freed themselves from their former overlords.

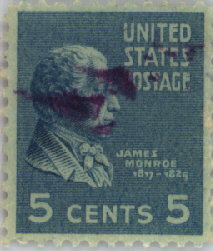

On

December 2, 1823, Monroe delivered to Congress his

annual message, several passages of which constitute the Monroe

Doctrine:

On

December 2, 1823, Monroe delivered to Congress his

annual message, several passages of which constitute the Monroe

Doctrine:

- "The American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers."

- "The political system of the allied powers is essentially different.. . from that of America... . We should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety."

- "With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere."

- "In the wars of the European powers in matters relating to themselves we have never taken any part, nor does it comport with our policy to do so."

While the Monroe Doctrine was clarifying American policy in world affairs, domestic interest was centered on the coming presidential campaign. A close contest among five candidates, including Andrew Jackson, the hero of the Battle of New Orleans, resulted in the election of John Quincy Adams, the son of John Adams, second President of the United States.

During the administration of John Quincy Adams, new party alignments were formed. Adams' followers took the name of "National Republicans," later to be changed to "Whigs." Though he governed honestly and efficiently, Adams was not a popular President, and his administration was marked with frustrations: among other things, he was thwarted in his effort to institute a national system of roads and canals. His years in office appeared to be one long campaign for reelection, and his coldly intellectual temperament did not win friends. Jackson, on the contrary, had enormous popular appeal, especially among his followers in the new Democratic Party; and, in the election of 1828, the Jacksonian forces overwhelmed Adams and his supporters.

The selfreliant backwoodsmen who had built the commonwealths west of the Alleghenies had written into their constitutions the democratic ideas of the frontier. By 1828, their philosophy had enfranchised masses of people in most of the older states. Since the war of 1812, the west had held the balance of power in the Union. Now, as the west came of age, the political center of gravity, like the center of population, had left the seaboard, and helped to place a favorite son of Tennessee in the Chief Executive's chair.