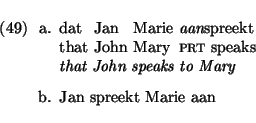

Certain verbs in Dutch subcategorize for a so-called ``separable prefix''. These particle-like elements appear as part of the verb in subordinate clauses, but appear in clause-final position if their governor heads a main clause:

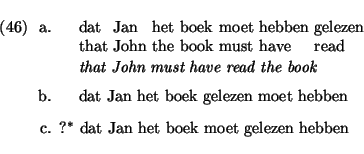

In complex verb-sequences, the prefix can appear not only as part of its governor, but also in positions further to the left:

In the analysis below, we assume that separable prefixes are selected as complements, and thus appear on the SUBCAT-list of the verbs introducing them (51). Such an analysis immediately accounts for example (50c). The phrase structure for this example is given in (52).

Cases in which the prefix is adjacent to its governor, or placed in some intermediate position, require a different analysis. When the prefix is adjacent to its governor, it is often assumed that the prefix has been incorporated by its governor. If we believe that this suggestion is on the right track, we could introduce a new rule schema to deal with this kind of ``incorporation'': 8

![\enumsentence{

{\sc Rule 2:}

\begin{avm}

\sort{word}{\begin{displaymath}~ \end{...

...}{\begin{displaymath}head & verb$[\neg$fin$]$\\

\end{displaymath}}

\end{avm}}](img55.png)

Rule 2 instantiates the general rule schema presented in section 2, and thus the Head-feature, Subcategorization, Nonlocal feature, and Directionality principle apply.9

The rule can be used to combine a non-finite head with a prefix, and gives rise to a complex constituent that is lexical instead of phrasal. The distinction between complements that can be prefixed and other complements is implemented using the boolean feature PFX. The default will be that elements of SUBCAT are -PFX, but that separable prefixes are +PFX.

Rule 2 is restricted to non-finite verbs for two reasons. First of all, this restriction prevents a spurious derivation of cases such as (50c), where the prefix can be considered to be an ordinary complement. Second, we must prevent the rule from applying in main clauses (49). If Rule 2 could apply on finite verbs (which may head main clauses) the ungrammatical (54) would be derivable.

The following word order constraint holds for Rule 2:

![\enumsentence{

The non-head daughter must be the most oblique element marked

[{\sc dir} {\em left}] on the {\sc subcat}-list of the head.

}](img58.png)

This constraint not only orders prefixes left of the head, but also introduces a limited amount of ordering freedom. In particular, prefixes are not only allowed to precede the verbs that introduce them (see (56)), but are also allowed to precede governors which ``inherit'' the prefix as argument (57).

While the word order constraint imposed on Rule 2 allows a prefix to appear in a number of positions within the verb cluster, at the same time, an important restriction on the position of ``inherited'' prefixes is obeyed. The restriction is illustrated in the examples below, in which inversion applies to participles selecting a prefix:

The derivation of the ungrammatical (58b) is excluded, as the prefix is not the most oblique [DIR left] element on SUBCAT of hebben (59), and thus Rule 2 cannot licence aan hebben as a complex lexical element. For the same reason, Rule 2 does not licence aan zou as a lexical element in (58c). Note also that a derivation of the latter example by means of Rule 1 is excluded, as this would imply a violation of the word order constraint for Rule 1, which says that if two complements occur left of the head, the most oblique complement should be closest to the head.

The word order constraint on Rule 2 has deliberately been formulated to allow prefixes to precede verbs which only ``inherit'' this prefix. Some speakers of Dutch, however, are reluctant to accept sentences in which a prefix appears in intermediate positions in the verb cluster. Such speakers do accept examples in which the prefix is adjacent to the verb introducing it, and also examples in which the prefix appears left of the finite verb, but they do not accept the word order in(60b)

This dialect can be described by imposing a more restrictive word order constraint on Rule 2. As it stands, the word order constraint requires that the selected prefix must be the most oblique [DIR left] element on SUBCAT. If the prefix is simply required to be the most oblique (i.e., the last) element on SUBCAT, Rule 2 can only apply to verbs which introduce the prefix. Remember that if a verb subcategorizes for a prefix via inheritance, the prefix can never be the last element on SUBCAT, and thus the ungrammaticality (in the restrictive dialect) of (60b) would be accounted for.

Finally, we come back to inversion with auxiliaries. Some speakers of Dutch accept not only instances of inversion with a governing auxiliary in which the governed participle occurs as the first element of the verb sequence, but also instances in which the participle occurs in intermediate positions left of the auxiliary. That is, such speakers also accept the word order in (61c).

As we pointed out above, a flat analysis of the verb cluster makes it easy to account

for the dialect in which only (61a) and (61b) are grammatical.

In dialects in which (61c) is grammatical as well, the position of participles in inverted word orders is highly similar to that of prefixes (in the standard dialect that accepts these in intermediate positions). Our suggestion is therefore that for dialects that accept the word order in (61c), participles are marked +PFX as well.