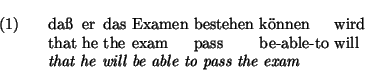

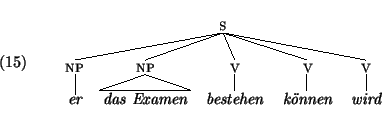

German subordinate clauses containing a cluster of a main verb and modal and/or auxiliary verbs, give rise to a nesting (or embedding) dependency word order:

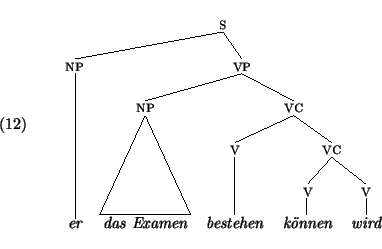

Hinrichs and Nakazawa [3,4] argue that the phenomenon known as Oberfeldumstellung or auxiliary flip (2) provides evidence for the fact that the complement of auxiliaries and modals (i.e. wird and können in (2) is not a full VP, but a constituent consisting of verbal material only.

![]()

If können were to select the VP das Examen

bestehen as complement, giving rise to a constituent which is

itself the complement of wird, the word order in (2)

would be completely unexpected. If können and wird are `complement inheritors', however,

an analysis suggests

itself in which bestehen können, but not das Examen

bestehen können is a constituent. The proposed lexical entries

for können and wird are given below:2

![\ex.

\a. \begin{avm}

{\rm k\uml onnen }({\em to be able to}) $\mapsto$ \avmjpro...

...\\

comps & \@1 \\

npcomps & -

\avmjpostlog]\>

\avmjpostlog]

\end{avm}\par](img6.png)

The NPCOMPS feature

plays a role in the following two HEAD-COMPLEMENT schemata:

![\ex.

\a. \begin{avm}

V\avmjprolog[npcomps & - \avmjpostlog]$~\rightarrow ~$\ H\a...

...vm}

V\avmjprolog[npcomps & + \avmjpostlog] $~\rightarrow ~$\ NP, H

\end{avm}\par](img7.png)

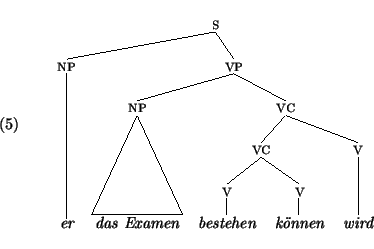

The first rule in (4) licenses the derivation of a

verbal complex, whereas the second rule licences the derivation of

(partial) verb phrases. Note that, in VPs with standard word

order, these two schemata give rise to a

binary, left-branching, tree:3

Auxiliary flip is accounted for by means of a binary

head feature FLIP. The following linear precedence

statement expresses that verbal complements marked [FLIP +] must

follow the head:

![\ex.

\begin{avm}

head\avmjprolog[lex & +\avmjpostlog] $~ < ~$\ complement\avmjprolog[maj & v \\ flip & + \avmjpostlog]

\end{avm}\par](img9.png)

Since main verbs never induce flipped word order, they are

considered to be marked [FLIP -]. Infinitival modals such as können are unspecified for the head feature FLIP. Thus,

given the constituent structure in (5) and the LP

statement in (6), it is predicted that both the word order in

(1) and in (2) is allowed.

A complication arises from the fact that können can also function as Ersatzinfinitiv (substitute infinitive).4 In those cases, flipped word order is obligatory. This fact is accounted for by assigning the Ersatzinfinitiv können the value [FLIP +]:

![\ex.

\begin{avm}

{\rm k\uml onnen }({\em to be able to}) $\mapsto$ \avmjprolog[...

...\

comps & \@1 \\

npcomps & -

\avmjpostlog] \>

\avmjpostlog]

\end{avm}\par](img10.png)

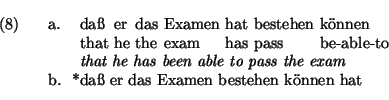

This accounts for the contrast in (8):

The auxiliary haben, finally, functions as a `trigger' for

flipped word order only in case it appears in `flipped' position

itself. This is illustrated in (9).

In (9)a, haben must precede singen

können, and therefore is a trigger for flipped word order itself.

In (9)c, haben does not appear in flipped position,

and consequently cannot trigger flipped word order for wird. This can be accounted for by assuming that haben

inherits the FLIP-value of its verbal complement:

![\ex.

\begin{avm}

{\rm haben }({\em to have}) $\mapsto$ \avmjprolog[ head & \avm...

...\

comps & \@1 \\

npcomps & -

\avmjpostlog] \>

\avmjpostlog]

\end{avm}\par](img13.png)

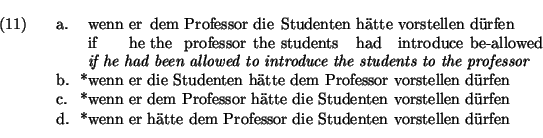

An essential aspect of the Hinrichs and Nakazawa account of word order within the verb cluster is the distinction between verbal complexes and other partial verb phrases expressed by the feature NPCOMPS. First, in sentences with `normal' word order, selection for a [NPCOMPS -] complement prevents ambiguity. That is, in those cases the [NPCOMPS -] specification on the complement ensures that the inheritance verb combines with a verb or verbal complex, rather than a full VP. Second, in sentences with `flipped' word order, the NPCOMPS feature ensures that the auxiliary `flips' only over the verbal complex, and not over a full or partial VP. This is illustrated in (11):

While the examples in (11)b-d are judged

grammatical by some speakers, other speakers reject such examples.

The fact that auxiliaries and modal verbs are complement inheritance verbs has been widely accepted. Questions concerning the constituency of phrases headed by such, however, have not been answered uniformly. In [6], for instance, it is argued that the verbal complex is right-branching instead of left-branching:

This analysis has the advantage that it is no longer

necessary to have two HEAD-COMPLEMENT schemata, one for creating

verbal complexes and a second rule for creating (partial) VPs. The feature NPCOMPS can dispensed with as

well. Instead, complement inheritance verbs select a verbal complement

which is marked +LEX. A problem for

this kind of analysis is obviously that there is no easy way to

account for auxiliary flip.

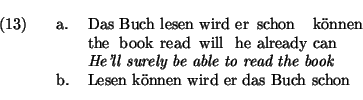

Proposals for a non-binary branching analysis have been put forward as well. In [11], for instance, it is argued that instances of partial VP fronting (13) are best accounted for by making minimal assumptions about the internal structure of VPs.

For transformational accounts, which assume a correspondence between a

fronted element and a trace in the remaining clause, such

examples are problematic. Only an analysis

that assigns multiple bracketings to das Buch lesen können can

account for the two examples in (13). However, such an analysis

must accept spurious ambiguity

in examples without fronting.

Nerbonne provides an alternative, nontransformational and traceless, account, in which a complement extraction lexical rule shifts an element from COMPS to SLASH. A special feature of this rule is that the requirement that a complement must be [NPCOMPS -] or +LEX is not carried over to SLASH. This essentially allows an complement inheritance verb, which normally selects for a verbal complex or lexical verb, to have an element on SLASH matching an arbitrary partial VP.

Nerbonne emphasizes that, given his analysis, fronting of partial VPs is no longer an argument for assigning constituent-status to such phrases in non-fronted positions as well. Consequently, there seems to be no reason why a verbal head could not combine with all its complements in one step. Although Nerbonne does not address this issue in detail, he suggests that an account of auxiliary flip still necessitates the introduction of a verbal complex. That is, an auxiliary could have a verbal complex as one of its arguments:

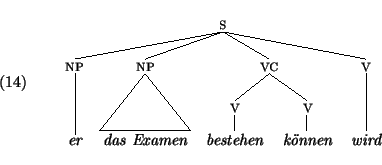

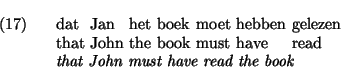

However, even the existence of verbal complexes can be

questioned. In [1], for instance, the example above is

assigned the following structure:

Flat structures of this kind can be obtained if complement inheritance

verbs select a lexical complement, and furthermore, the HEAD-COMPLEMENT schema imposes the constraint that the head must be

lexical (i.e. of type word). It should be noted, however, that

Baker tries to account for auxiliary flip by assuming that in those cases the

auxiliary takes a partial VP as argument. As is admitted by

Baker herself, such an account overgenerates, as it not

only accepts ordinary cases of auxiliary flip, but also all of the

examples in (11) and even such sequences as

(16), which are completely ungrammatical:

The proposal of

[4] deals succesfully with auxiliary flip in

the German verb cluster. Alternatives which also explicitly address

this issue, such as [1], are not without problems.

This does not imply, however, that alternatives are not worth

considering. For one thing, while the analysis of Hinrichs and

Nakazawa leads to a smooth account of auxiliary flip, it cannot easily

account for some other word order patterns.

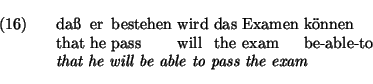

In Dutch subordinate clauses, for instance, the presence of auxiliaries and modals also leads to a cluster of verbs in clause-final position. The standard order in this case, however, is one where the governing verb precedes the verb it governs:

As in German, a certain amount of word order variation is

permitted. The participle in (17), for instance, may also be

the first element in the cluster:

![]()

An analysis which assigns constituent status to gelezen hebben

cannot easily account for this possibility.

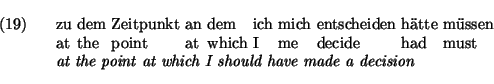

Of course, it may be that constituency within the verb cluster in Dutch is simply different than in German. However, there are also German examples which appear to be problematic. Meurers [9] has drawn attention to the following examples, which he refers to as cases of Zwischenstellung:

The analysis of [4]

considers entscheiden

müssen as a constituent. The fact that hätte may, for a

considerable number of speakers, `flip' over the modal verb only in

this case, is cleary problematic for their analysis.

Below, we develop an alternative analysis for the German verb cluster. It not only handles auxiliary flip, but also Zwischenstellung. An advantage of our `flat' analysis is that it uses a single HEAD-COMPLEMENT schema to derive both full and partial VPs, without spurious ambiguity. In previous work [18], we argued that this means that a single rule can account for the derivation of full VPs as well as the kind of partial VPs encountered in examples of partial VP fronting and partial extraposition (third construction) in Dutch. Thus, the alternative developed below accounts for a wider range of data, and does so by using fewer rules, than previous proposals. Moreover, there is no need for a feature such as NPCOMPS. This is advantageous because the percolation of this feature in previous analyses is rather peculiar and not subject to one of the ordinary feature percolation constraints (such as the head feature principle).