In this section we revise and extend the analysis of Dutch presented in [18].

As in German, Dutch subordinate clauses are verb-final. If the clause is headed by a modal, an auxiliary, or a verb such as horen (to hear), proberen (to try), helpen (to help) or laten (to let) (these are so-called `verb-raising' verbs), the head of its non-finite VP-complement must occur right of the head of the main clause. This is illustrated in (51-c)a,b. As the head of the non-finite VP can be a verb-raising verb itself, the construction can (in principle) lead to an arbitrary number of crossing dependencies between pre-verbal complements and verbs subcategorizing for these complements. This is illustrated in (51-c)c, where subscripts are used to make the dependencies explicit.

Following our proposals for German in the prevous section, we assume that Dutch `verb-raising' verbs select for a list of complements consisting of a verb and the complements selected by that verb. The word order constraints for complement-inheritance verbs make reference to GVOR. Furthermore, complement-inheritance verbs select an i-zone complement. Some lexical elements are given below.

![\ex.

\a.

\begin{avm}

{\rm willen} ({\em to want}) $\mapsto$ \avmjprolog[ head ...

...w$\ \avmjpostlog]

\> \\

arg-s & \<\@2,\@3,\@4\>

\avmjpostlog]

\end{avm}\par](img59.png)

Note that directionality only orders complements relative to

the head; the order of complements with respect to each other is left

open. In previous work on Dutch [18],

we have assumed that obliqueness

provides an ordering of complements: if C1 is more

oblique than C2 (i.e. the SYNSEM-value of) C1 follows

C2 on COMPS), than C1 appears closer to the head than

C2. For German, we have been

satisfied with the assumption that the order of non-verbal o-zone

complements is not (only) determined by obliqueness. For Dutch,

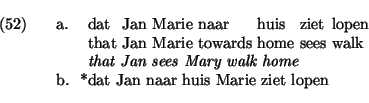

this appears to be much less likely. Consider the example in

(53), for instance. The perception verb zien is an

complement-inheritance verb selecting for a verbal complement and an

NP object (Marie). Both the NP Marie and the

PP naar huis are o-zone complements of the head ziet. The order of both is strictly determined by the order on COMPS, however.

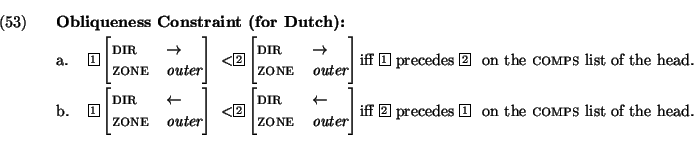

This suggests that the Obliqueness word order constraint

must apply for o-zone elements. This constraint,

applicable to Dutch, is given in (54).

A derivation for the VP of example (51-c)c

can now be given as follows:

![\ex.

{\sc

\begin{tabular}[t]{ccccc}

\multicolumn{5}{c}{

\node{vp1-vp}{vp$\lang...

...1}{vp1-wil}

\nodeconnect{vp1-v2}{vp1-laten}

\nodeconnect{vp1-v3}{vp1-lezen}

\par](img62.png)

The word order given in this example is the only grammatical

word order, and the only word order allowed by the analysis. This is

so, because the NPs are ordered to the left of the verbs

because of directionality; the order of the NPs is

determined by obliqueness; and the order of the verbs is determined by

the Governor Constraints.

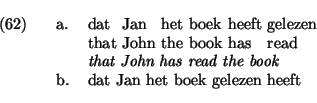

In comparison with the analysis presented in [18], the introduction of governor word order constraints has no consequences for the word orders that can or cannot be derived in the case of ordinary verb raising verbs. 16

It is more interesting for cases where governors and governees do not appear in strict left-to-right order, as in participle inversion constructions and in constructions involving separable prefixes.

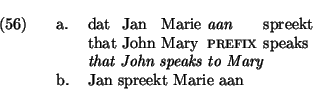

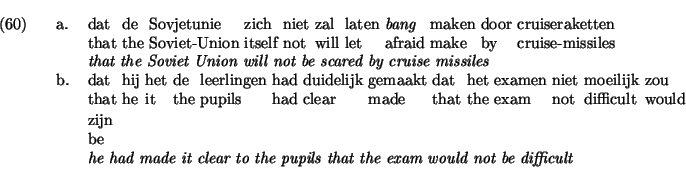

Certain verbs in Dutch subcategorize for a so-called `separable prefix'. These particle-like elements appear as part of the verb in subordinate clauses, but appear in clause-final position if their governor heads a main clause:

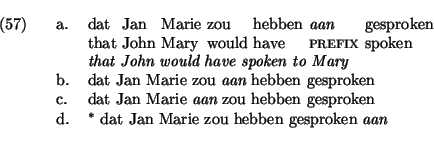

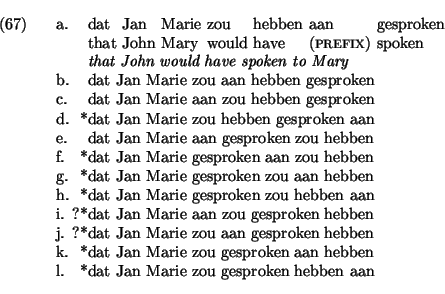

In complex verb-sequences, the prefix can appear not only as part of

its governor, but also in positions further to the left:

These examples can now be treated straightforwardly.

A verb selecting a separable prefix requires this

prefix to be [GVOR

![]() , i-zone]. This predicts correctly

that this prefix can occur anywhere to the left of the governing verb

within the verb cluster. The lexical entry for spreken and an example

derivation are given below.

, i-zone]. This predicts correctly

that this prefix can occur anywhere to the left of the governing verb

within the verb cluster. The lexical entry for spreken and an example

derivation are given below.

![\ex.

\begin{tabular}[t]{ccccc}

\multicolumn{4}{c}{

\node{nlpart-vp}{vp$\langle\...

...connect{nlpart-v1}{nlpart-hebben}

\nodeconnect{nlpart-v2}{nlpart-gesproken}

\par](img67.png)

Note that apart from the word order given in

(59), the orders aan zou hebben gesproken and zou hebben aan gesproken are derivable as well.

The verb-cluster sometimes also contains an adjective. The following examples are similar to a large set of examples given in [2]:

The adjective can be placed at any position left of its

governor, just like separable prefixes. The difference with compound verbs

which require a separable prefix is not always easy to make.

Such examples are not treated as compound verbs in [2].

Interestingly, such verbs can often take a full adjectival phrase instead of a single adjective. In those cases, however, the ADJP cannot be part of the verb cluster:

These examples can be analysed straightforwardly by assuming that certain verbs subcategorize for an adjectival phrase. Those verbs do not constrain the ZONE feature of this adjectival phrase. This implies that if such an ADJP is selected in the I-ZONE, it must be a word; if it is selected as part of the O-ZONE it can be either a word or a full phrase.

In more complex examples, the pattern is that the participle is either

to the left of the finite verb, or the last verb of the cluster:

![]()

are acceptable only to a minority of speakers.

The analysis of these examples proceeds as follows. For those speakers that accept examples such as (64), we assume that the lexical entry for hebben leaves the GVOR value of its complement unspecified:

![\ex.

\begin{avm}

{\rm hebben }({\em to want}) $\mapsto$ \avmjprolog[ head & ve...

...\

comps & \@1 \\

zone & inner \avmjpostlog] \>

\avmjpostlog]

\end{avm}\par](img73.png)

This results in a situation in which the participle may occur

anywhere left of the auxiliary within the cluster:

both (63)a, (63)b and (64) are derivable.

For the standard dialect we assume that the participle may only precede the governing auxiliary if it also precedes the head. Thus, the features for directionality and governor must agree. A modified lexical entry which implements this constraint is given below:

![\ex.

\begin{avm}

{\rm hebben} ({\em to want}) $\mapsto$ \avmjprolog[ head & ve...

...er \\

gvor & \@2 \\

dir & \@2 \avmjpostlog] \>

\avmjpostlog]

\end{avm}\par](img74.png)

Note that the reentrancy between GVOR and

DIR avoids the introduction of two separate lexical entries

(i.e. one for the situation where the participle follows the

auxiliary, and one for the situation where it precedes it). In

(64), the participle gelezen precedes its governor,

but follows the head of the phrase (i.e. zou), and thus no

derivation on the basis of the modified lexical entry for hebben

is possible.

Summarizing, this analysis correctly predicts the following set of facts, involving both a separable prefix and a participle:

The most interesting cases are the pairs (67)e,f and

(67)i,j. Example (e) is allowed, because the prefix aan

precedes its governor gesproken; in (f) this is not the case,

hence this example is ruled out. The examples (i) and (j) are allowed

only in those dialects which allow (64).