[67] proposes a grammatical formalism called Head

Grammar (HG). HG is a slightly more powerful formalism than

context-free grammar. The extra power is available through head

wrapping operations. A head wrapping operation manipulates strings

which contain a distinguished element (its head). Such headed strings are a pair of an ordinary string, and an index (the

pointer to the head), for example

![]() w1w2w3w4, 3

w1w2w3w4, 3![]() is

the string

w1w2w3w4 of which the head is w3. Grammar rules

define operations on such strings. Such an operation takes n headed

strings as its arguments and returns a headed string. A simple example

is the operation which takes two headed strings and concatenates the

first one to the left of the second one, and where the head of the

first one is the head of the result (this shows that the operations

subsume ordinary concatenation). The rule is labelled LC1 by Pollard:

is

the string

w1w2w3w4 of which the head is w3. Grammar rules

define operations on such strings. Such an operation takes n headed

strings as its arguments and returns a headed string. A simple example

is the operation which takes two headed strings and concatenates the

first one to the left of the second one, and where the head of the

first one is the head of the result (this shows that the operations

subsume ordinary concatenation). The rule is labelled LC1 by Pollard:

![]()

The following example shows that head-wrapping operations are in

general more powerful than concatenation. In this example the second

argument is `wrapped' around the first argument:

![]()

As an example, Pollard presents a rule for English auxiliary

inversion:

![]()

which may combine the noun phrase `Kim' and the verb phrase `must go'

to yield `Must Kim go', with head `must'.

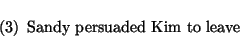

The motivation Pollard presents for extending context-free grammars (in fact, GPSG), is of a linguistic nature. Especially so-called discontinuous constituencies can be handled by HG whereas they constitute typical puzzles for GPSG. Apart from the above mentioned subject-auxiliary inversion he discusses the analysis of `transitive verb phrases' based on [8]. The idea is that in sentences such as

`persuaded' + `to leave' form a (VP) constituent, which then combines with the NP object

('Kim') by a wrapping operation.

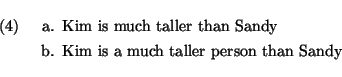

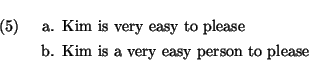

Yet another example of the use of head-wrapping in English are the analyses of the following sentences.

where in the first two cases `taller than Sandy' is a constituent, and

in the latter examples `easy to please' is a constituent.

Breton and Irish are VSO languages, for which it has been claimed that the V and the O form a constituent. Such an analysis is readily available using head wrapping, thus providing a non-transformational alternative for the analysis of [56].

Finally, Pollard also provides a wrapping analysis of Dutch cross-serial dependencies.