From Carillon to IBM

The musical roots of information technology

3. Repinnable cylinders

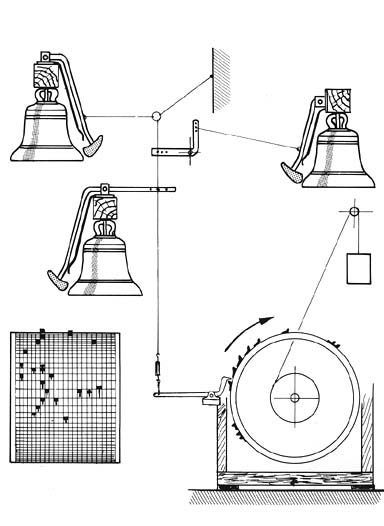

Carillon melodies were coded on a big iron cylinder (later replaced by brass) in the form of pins that could move levers connected to a bell. This was the first technology taking full advantage of the information storing capacity of the camshaft, with the rotation controlled by the clockwork. This art, culminating in the 17th century, became particularly popular in the Low Countries (Holland and Belgium), where every major church tower has a cylinder-controlled automatic carillon up till the present day. Schematically, it works as follows (courtesy Museum Guide of the Utrecht museum):

The dark dots on the drum (bottom left) are the pins and on the right you see how the pins can hit a lever connected to a hammer that can strike a bell.

This kind of automaton is like what everyone knows from musical boxes,

with the sounds produced by tuned bells rather than by the teeth of

a tuned comb. Hower, these turret automata are not only much bigger

than what you find in musical boxes, they are in a very significant

sense also more sophisticated (for a giant real-life example,

click

here). Unlike the

cylinders of musical boxes, these carillon cylinders are repinnable,

thereby allowing the programming of different melodies. The Utrecht

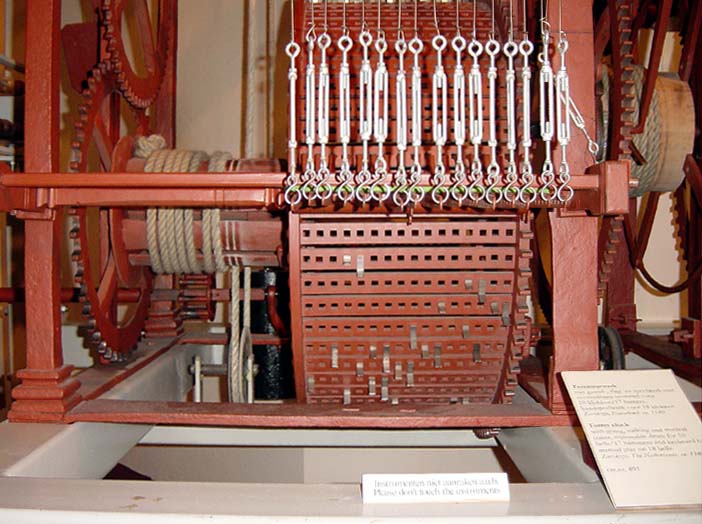

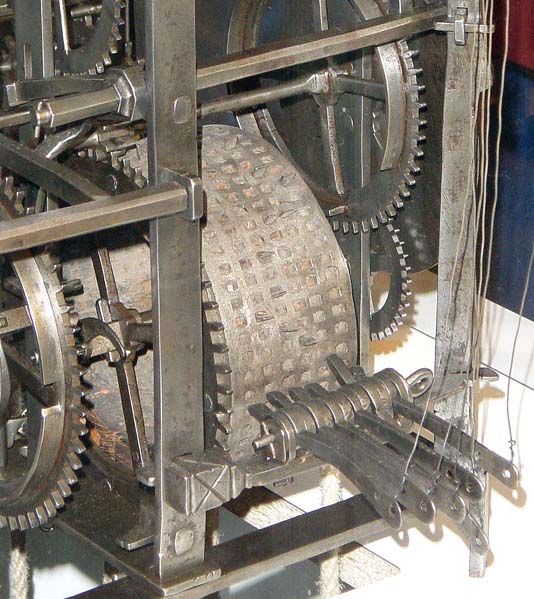

museum has a model of which I took the pictures you see here. In

these pictures, you can see that each hole on the drum corresponds with

a lever, connected to a steel cable that leads to a bell. In terms of

information representation, then, each hole on the drum corresponds

to a sound. Especially on the second picture (below), you can see how the programming works: the pins can be screwed

into different holes, so that different bells will sound (or not) whenever

a row of holes passes the levers. If we project the cylinder surface

onto a plane, we can say that rows (of holes) represent the

presence or absence of bell sounds

and columns represent points in time (the

rotation speed of the cylinder being controlled by the connected clock).

took the pictures you see here. In

these pictures, you can see that each hole on the drum corresponds with

a lever, connected to a steel cable that leads to a bell. In terms of

information representation, then, each hole on the drum corresponds

to a sound. Especially on the second picture (below), you can see how the programming works: the pins can be screwed

into different holes, so that different bells will sound (or not) whenever

a row of holes passes the levers. If we project the cylinder surface

onto a plane, we can say that rows (of holes) represent the

presence or absence of bell sounds

and columns represent points in time (the

rotation speed of the cylinder being controlled by the connected clock).

It is important at this point to appreciate that there is no conceptual

difference between this kind of information representation in metal

and the later forms of representation with perforated paper (punched

cards). The repinnable drums of our carillons since the Middle Ages

are automata programmable in the true sense, with the information representation

(of music in this case), as in punched cards, depending on the distribution of interpretable points

on a “map” of columns and rows.

It should be noted that from the beginning this kind of information representation was not limited to the programming of music. Modern information media, like the earlier punched cards and present day CDs, store information in an abstract way, so that lots of different things, from numerical data to images and sounds, can be represented by the same means. The differences depend on the various forms of external interpretation, for instance by a sound board or by a graphic card, etc.

It is obvious that the kind of late medieval automaton described here can also be used to program things other than music, namely by connecting the levers to altogether different things. And so it in fact happened right from the beginning. Already in the earliest turret clockworks, levers were not only connected to bells but also to figurines performing certain actions. These are known as Jacquemarts or Clock Jacks: little men hitting a bell with a hammer to indicate the hour. Jacquemarts are found in tower clockworks all over Europe, but they also found their way to small-format chamber clocks. The Utrecht museum has a nice late-Gothic exemplar from the Southern Netherlands of c.1480. This clock has, next to the two Jacquemarts, six bells controlled by a repinnable cylinder:

Repinnable cylinders were mainly used for clocks with bells, but, also non-repinnable cylinders were applied in many other ways: to animate puppets or to operate fountains and water gadgets, like the famous waterworks built for Archbishop Markus Sitticus in Hellbrunn (near Salzburg) around 1646.

Next to the carillon (and before the late 18th-century invention of the musical box), the most famous musical application of cylinder programming can be found in automatic organs. Like the automatic carillons, they were already developed since the 14th century and they are usually of the non-repinnable kind (and as such more like a musical box). In these cases, the driving mechanism (weights and, after their invention in the 15th century, also springs) not only has to keep the clockwork going but also one or more bellows to provide the wind for the organ pipes (bellows (white) on top of the cylinder):

These automatic organs were immensely popular, also among great composers like Handel, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, who composed music for automata and who actively participated in the design of numerous cylinders to make some extra money. The musicological significance of this heritage, with original evidence of tempi, etc., is immense.

All in all, then, there was a rich tradition in Europe of mechanical,

programmable automata from the late Middle Ages to the early 20th

century. This form of automation was mainly applied to musical instruments

but also to numerous other gadgets and objects

to be animated

<<previous

1

|

2| 3|

4|

5|

next>>