Many Cultures Blend

After 1680 large numbers of immigrants came from Germany, Ireland, Scotland, Switzerland and France; and England ceased to be the chief source of immigration. Again, the new settlers came for various reasons. Thousands fled from Germany to escape the path of war. Many left Ireland to avoid the poverty induced by government oppression and absentee-landlordism, and from Scotland and Switzerland, too, people came fleeing the specter of poverty. By 1690, the American population had risen to a quarter of a million. From then on, it doubled every 25 years until, in 1775, it numbered more than two and a half million.

For the the most part, non-English colonists adapted themselves to the culture of the original settlers. But this did not mean that all settlers transformed themselves into Englishmen. True, they adopted the English language and law and many English customs, but only as these had been modified by conditions in America. The result was a unique culture-a blend of English and continental European conditioned by the environment of the New World.

Although a man and his family could move from Massachusetts to Virginia, or from South Carolina to Pennsylvania, without making many basic readjustments, distinctions between individual colonies were marked. They were even more marked between regional groups of colonies.

The settlements fell into fairly well-defined sections determined by geography. In the south, with its warm climate and fertile soil, a predominately agrarian society developed. New England in the northeast, a glaciated area strewn with boulders, was inferior farm country, with generally thin, stony soil, relatively little level land, short summers, and long winters. Turning to other pursuits, the New Englanders harnessed water power and established gristmills and sawmills. Good stands of timber encouraged shipbuilding. Excellent harbors promoted trade, and the sea became a source of great wealth. In Massachusetts, the cod industry alone quickly furnished a basis for prosperity.

For a map of the colonial period click here

Settling in villages and towns around the harbors, New

Englanders quickly adopted an urban existence, many of them

carrying on some trade or business. Common pastureland and common

wood-lots served the needs of townspeople, who worked small

farms nearby. Compactness made possible the village school, the

village church, and the village or town hall, where citizens met

to discuss matters of common interest. Sharing hardships,

cultivating the same rocky soil, pursuing simple trades and crafts,

- New Englanders rapidly acquired characteristics that marked them

as a self-reliant, independent people.

Settling in villages and towns around the harbors, New

Englanders quickly adopted an urban existence, many of them

carrying on some trade or business. Common pastureland and common

wood-lots served the needs of townspeople, who worked small

farms nearby. Compactness made possible the village school, the

village church, and the village or town hall, where citizens met

to discuss matters of common interest. Sharing hardships,

cultivating the same rocky soil, pursuing simple trades and crafts,

- New Englanders rapidly acquired characteristics that marked them

as a self-reliant, independent people.

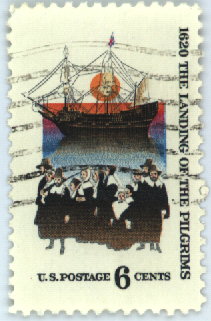

These qualities had manifested themselves in the 102 seaweary Pilgrims who first landed on the peninsula of Cape Cod, projecting into the Atlantic from southeastern Massachusetts. They had sailed to America under the auspices of the London (Virginia) Company and were thus intended for settlement in Virginia, but their ship, the Mayflower made its landfall far to the north. After some weeks of exploring, the colonists decided not to make the trip to Virginia but to remain where they were. They chose the area near Plymouth harbor as a site for their colony, and though the rigors of the first winter were severe, the settlement survived.