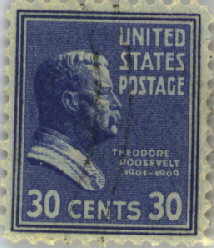

Roosevelt Acts To Save Resources

Conservation of the nation's natural resources, putting an

end to wasteful exploitation of raw materials, and the reclamation

of wide stretches of neglected land were among the major

achievements of the Roosevelt era. Roosevelt had called for a

far-reaching and integrated program of conservation, reclamation, and

irrigation as early as 1901 in his first annual message to Congress.

Whereas his predecessors had set aside 18,800,000 hectares of

timberland, Roosevelt increased the area to 59,200,000 hectares

and began systematic efforts to prevent forest fires and to

retimber denuded tracts.

Whereas his predecessors had set aside 18,800,000 hectares of

timberland, Roosevelt increased the area to 59,200,000 hectares

and began systematic efforts to prevent forest fires and to

retimber denuded tracts.

In 1907, Roosevelt appointed an Inland Waterways Commission to study the relation of rivers, soil, and forest, waterpower development and water transportation. Out of the recommendations of this Commission grew the plan for a national conservation conference, which focused the nation's attention upon the need for conservation.

The Commission's declaration of principles stressed the conservation of forests, water and minerals, and addressed itself to the problems of soil erosion and irrigation. Its recommendations included the regulation of timbercutting on private lands, the improvement of navigable streams, and the conservation of watersheds. As a result, many states established conservation commissions, and, in 1909, a National Conservation Association was formed to educate the public on the subject. In 1902, the Reclamation Act was passed, authorizing the creation of a number of large dams and reservoirs.

Roosevelt's popularity was at its peak as the campaign of 1908 neared, but he was unwilling to break the tradition by which no President had held office for more than two terms. Instead, he supported William Howard Taft, who won the election and sought to continue the Rooseveltian program. Taft made some forward steps. He continued the prosecution of trusts, further strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission, established a postal-savings bank and a parcel-post system, expanded the civil service, and sponsored the enactment of two amendments to the national Constitution.

The Sixteenth Amendment authorized a federal income tax; the Seventeenth Amendment, ratified in 1913, substituted the direct election of Senators by the people for the requirement that they be elected by state legislatures. Yet balanced against these achievements was Taft's acceptance of a tariff with protective schedules that outraged liberal opinion; his opposition to the entry of the state of Arizona into the Union because of its liberal constitution; and his growing reliance on the ultraconservative wing of his party.

By 1910 Taft's party was divided, and an overwhelming vote swept the Democrats back into control of Congress. Two years later, Woodrow Wilson, governor of the state of New Jersey, campaigned against Taft, the Republican candidate, and against Roosevelt who, rejected as a candidate by the Republican convention, had organized a third party, the Progressives.

Wilson, in a spirited campaign, defeated both rivals. Under his leadership the new Congress proceeded to put through one of the most notable legislative programs in American history. Its first task was tariff revision. "The tariff duties must be altered," Wilson said. "We must abolish everything that bears any semblance of privilege." The Underwood tariff, signed on October 3, 1913, provided substantial rate reductions on important raw materials and foodstuffs, cotton and woolen goods, iron and steel, and it removed the duties from more than a hundred other items. Although the act retained many protective features, it was a genuine attempt to lower the cost of living.

The second item on the Democratic program was a long-overdue, thorough reorganization of the inflexible banking and currency system, which had limped along on emergency currency issued by stopgap legislation. "Control," said Wilson, "must be public, not private, must be vested in the government itself, so that the banks may be the instruments, not the masters, of business and of individual enterprise and initiative."

The Federal Reserve Act of December 23, 1913, satisfied Wilson's requirements. It imposed upon the existing banks a new organization that divided the country into 12 districts, with a Federal Reserve Bank in each, all supervised by a Federal Reserve Board. These banks were to serve as depositories for the cash reserves of those banks that joined the &ystem. To assure greater flexibility in the money supply, provision was made for issuing federal reserve notes to meet business demands.

The next important task was trust regulation and investigation of corporate abuses. Experience suggested a system of control similar to that of the Interstate Commerce Commission over the railways. A Federal Trade Commission was authorized to issue orders prohibiting "unfair methods of competition" by business concerns in interstate trade. A second law, the Clayton Antitrust Act, forbade many corporate practices that had thus far escaped specific condemnation-interlocking directorates, price discrimination among purchasers, and ownership by one corporation of stock in similar enterprises.

Farmers and labor were not forgotten. A Federal Farm Loan Act made credit available to farmers at low rates of interest. One provision of the Clayton Act specifically prohibited use of the injunction in labor disputes. The Seamen's Act of 1915 provided for improving employees' living and working conditions on ocean-going vessels and on lake and river craft. The Federal Workingman's Compensation Act in 1916 authorized allowances to civil service employees for disabilities incurred at work. The Adamson Act of the same year established an eight-hour day for railroad labor.

Though this record of achievement stemmed directly from President Wilson's leadership, Wilson's place in history is due not so much to his devotion to social reform as to the strange destiny that catapulted him into the role of wartime President and architect of the uneasy peace that followed World War I.