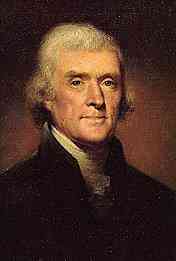

To Horatio G. Spafford Monticello, May 14, 1809

SIR,

SIR,-- I have duly received your favor of April 3d, with the copy of your "General Geography," for which I pray you to accept my thanks. My occupations here have not permitted me to read it through, which alone could justify any judgment expressed on the work. Indeed, as it appears to be an abridgment of several branches of science, the scale of abridgment must enter into that judgment. Different readers require different scales according to the time they can spare, and their views in reading, and no doubt that the view of the sciences which you have brought into the compass of a 12mo volume will be accommodated to the time and object of many who may wish for but a very general view of them

In passing my eye rapidly over parts of the book, I was struck with two passages, on which I will make observations, not doubting your wish, in any future edition, to render the work as correct as you can. In page 186 you say the potatoe is a native of the United States. I presume you speak of the Irish potatoe. I have inquired much into the question, and think I can assure you that plant is not a native of North America. Zimmerman, in his "Geographical Zoology," says it is a native of Guiana; and Clavigero, that the Mexicans got it from South America, its native country. The most probable account I have been able to collect is, that a vessel of Sir Walter Raleigh's, returning from Guiana, put into the west of Ireland in distress, having on board some potatoes which they called earth-apples. That the season of the year, and circumstance of their being already sprouted, induced them to give them all out there, and they were no more heard or thought of, till they had been spread considerably into that island, whence they were carried over into England, and therefore called the Irish potatoe. From England they came to the United States, bringing their name with them.

The other passage respects the description of the passage of the Potomac through the Blue Ridge, in the Notes on Virginia. You quote from Volney's account of the United States what his words do not justify. His words are, "on coming from Fredericktown, one does not see the rich perspective mentioned in the Notes of Mr. Jefferson. On observing this to him a few days after, he informed me he had his information from a French engineer who, during the war of Independence, ascended the height of the hills, and I conceive that at that elevation the perspective must be as imposing as a wild country, whose horizon has no obstacles, may present." That the scene described in the "Notes" is not visible from any part of the road from Fredericktown to Harper's ferry is most certain. That road passes along the valley, nor can it be seen from the tavern after crossing the ferry; and we may fairly infer that Mr. Volney did not ascend the height back of the tavern from which alone it can be seen, but that he pursued his journey from the tavern along the high road. Yet he admits, that at the elevation of that height the perspective may be as rich as a wild country can present. But you make him "surprised to find, by a view of the spot, that the description was amazingly exaggerated." But it is evident that Mr. Volney did not ascend the hill to get a view of the spot, and that he supposed that that height may present as imposing a view as such a country admits. But Mr. Volney was mistaken in saying I told him I had received the description from a French engineer. By an error of memory he has misapplied to this scene what I mentioned to him as to the Natural Bridge. I told him I received a drawing of that from a French engineer sent there by the Marquis de Chastellux, and who has published that drawing in his travels. I could not tell him I had the description of the passage of the Potomac from a French engineer, because I never heard any Frenchman say a word about it, much less did I ever receive a description of it from any mortal whatever. I visited the place myself in October 1783, wrote the description some time after, and printed the work in Paris in 1784-5. I wrote the description from my own view of the spot, stated no fact but what I saw, and can now affirm that no fact is exaggerated. It is true that the same scene may excite very different sensations in different spectators, according to their different sensibilities. The sensations of some may be much stronger than those of others. And with respect to the Natural Bridge, it was not a description, but a drawing only, which I received from the French engineer. The description was written before I ever saw him. It is not from any merit which I suppose in either of these descriptions, that I have gone into these observations, but to correct the imputation of having given to the world as my own, ideas, and false ones too, which I had received from another. Nor do I mention the subject to you with a desire that it should be any otherwise noticed before the public than by a more correct statement in any future edition of your work.

You mention having enclosed to me some printed letters announcing a design in which you ask my aid. But no such letters came to me. Any facts which I possess, and which may be useful to your views, shall be freely communicated, and I shall be happy to see you at Monticello, should you come this way as you propose. You will find me engaged entirely in rural occupations, looking into the field of science but occasionally and at vacant moments.

I sowed some of the Benni seed the last year, and distributed some among my neighbors; but the whole was killed by the September frost. I got a little again the last winter, but it was sowed before I received your letter. Colonel Fen of New York receives quantities of it from Georgia, from whom you may probably get some through the Mayor of New York. But I little expect it can succeed with you. It is about as hardy as the cotton plant, from which you may judge of the probability of raising it at Hudson.

I salute you with great respect.