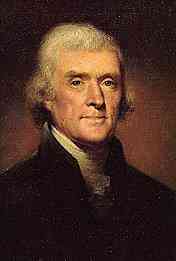

To John Garland Jefferson Monticello, January 25, 1810

DEAR SIR,

DEAR SIR,-- Your favor of December 12th was long coming to hand. I am much concerned to learn that any disagreeable impression was made on your mind, by the circumstances which are the subject of your letter. Permit me first to explain the principles which I had laid down for my own observance. In a government like ours, it is the duty of the Chief Magistrate, in order to enable himself to do all the good which his station requires, to endeavor, by all honorable means, to unite in himself the confidence of the whole people. This alone, in any case where the energy of the nation is required, can produce a union of the powers of the whole, and point them in a single direction, as if all constituted but one body and one mind, and this alone can render a weaker nation unconquerable by a stronger one. Towards acquiring the confidence of the people, the very first measure is to satisfy them of his disinterestedness, and that he is directing their affairs with a single eye to their good, and not to build up fortunes for himself and family, and especially, that the officers appointed to transact their business, are appointed because they are the fittest men, not because they are his relations. So prone are they to suspicion, that where a President appoints a relation of his own, however worthy, they will believe that favor and not merit was the motive. I therefore laid it down as a law of conduct for myself, never to give an appointment to a relation. Had I felt any hesitation in adopting this rule, examples were not wanting to admonish me what to do and what to avoid. Still, the expression of your willingness to act in any office for which you were qualified, could not be imputed to you as blame. It would not readily occur that a person qualified for office ought to be rejected merely because he was related to the President, and the then more recent examples favored the other opinion. In this light I considered the case as presenting itself to your mind, and that the application might be perfectly justifiable on your part, while, for reasons occurring to none perhaps, but the person in my situation, the public interest might render it unadvisable. Of this, however, be assured that I consider the proposition as innocent on your part, and that it never lessened my esteem for you, or the interest I felt in your welfare.

My stay in Amelia was too short, (only twenty-four hours,) to expect the pleasure of seeing you there. It would be a happiness to me any where, but especially here, from whence I am rarely absent. I am leading a life of considerable activity as a farmer, reading little and writing less. Something pursued with ardor is necessary to guard us from the tedium-vitae, and the active pursuits lessen most our sense of the infirmities of age. That to the health of youth you may add an old age of vigor, is the sincere prayer of

Yours, affectionately.