|

The previous section presented an argument that VP modifiers are selected for by the verb. Note that this is in line with earlier analyses of adjuncts in HPSG [6] which where abandoned as it was unclear how the semantic contribution of adjuncts could be defined.

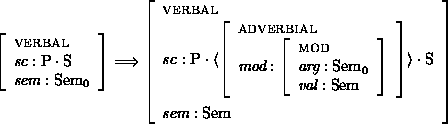

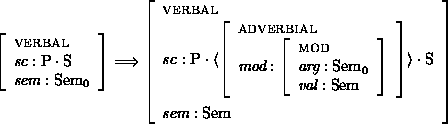

Here we propose a solution in which adjuncts are members of the subcat list, just like ordinary arguments. The difference between arguments and adjuncts is that adjuncts are `added' to a subcat list by a lexical rule that operates recursively.1 Such a lexical rule might for example be stated as in figure 3.

|

Note that in this rule the construction of the semantics of a modified verb-phrase is still taken care of by a mod feature on the adjunct, containing a val and arg attribute. The arg attribute is unified with the `incoming' semantics of the verb-phrase without the adjunct. The val attribute is the resulting semantics of the verb-phrase including the adjunct. This allows the following treatment of the semantics of modification 2, cf. figure 4. Restrictive adverbials (such as locatives and time adverbials) will generally be encoded as presented, where R0 is a meta-variable that is instantiated by the restriction introduced by the adjunct. Operator adverbials (such as causatives) on the other hand introduce their own quantified state of affairs. Such adverbials generally are encoded as in the following example of the adverbial `toevallig' (accidentally). Adverbials of the first type add a restriction to the semantics of the verb; adverbials of the second type introduce a new scope of modification

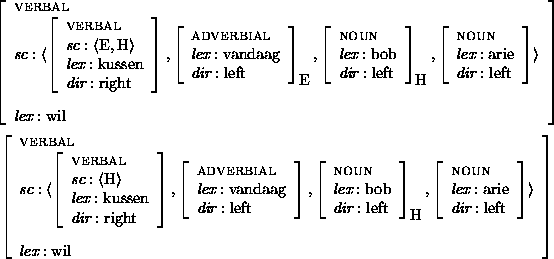

We are now in a position to explain the observed ambiguity of adjuncts in verb-cluster constructions. Cf.:

In the narrow-scope reading the adjunct is first added to the subcat

list of `kussen' and then passed on to the subcat list of the

auxiliary verb. In the wide-scope reading the adjunct is added to the

subcat list of the auxiliary verb. The final instantiations of the

auxiliary `wil' for both readings are given in figure 5.

|