In previous work on German verb clusters, various constituent structures for both the verb cluster and the VP have been proposed. None of the accounts presented so far appears to cover all the relevant data.

Hinrichs and Nakazawa [3,4] argue that the phenomenon known as Oberfeldumstellung or auxiliary flip (example (1b), repeated as (7) below) provides evidence for the fact that modals and auxiliaries must be `argument-inheritance' verbs.

If können would select the full VP das Examen bestehen as complement, giving rise to a constituent which is itself the complement of wird, the word order in (7) would be completely unexpected. If können and wird are assigned the `argument-inheritance' lexical entries in (8), however, an analysis suggests itself in which bestehen können, but not das Examen bestehen können is a constituent.4

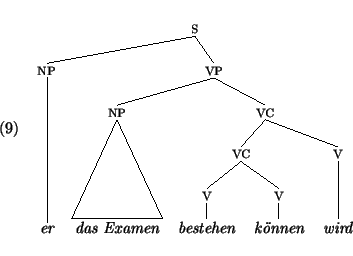

In particular, Hinrichs and Nakazawa distinguish between a verb cluster (VC) and a verb phrase. The verb cluster is a subconstituent of the VP, containing verbal elements only. Hinrichs and Nakazawa present a binary-branching analysis, in which the verb cluster, in cases with standard word order, is left-branching:5

Auxiliary flip is handled by means of a binary feature FLIP. If auxiliaries select a verbal complement marked as [FLIP +], the auxiliary must precede that complement.

In Hinrichs and Nakazawa's account, verb clusters are partial VP's marked as [NPCOMPS -], while VP's containing non-verbal complements are marked [NPCOMPS +]. Two separate rule schemata (one in which a lexical head selects a verbal ([NPCOMPS -]) complement, and one in which a head selects an NP (or other non-verbal complement)) are needed to implement the distribution of this feature. The distinction between verb clusters and other partial VP's is essential, as otherwise nothing would prevent an auxiliary to precede a complement consisting of a full VP:

Such examples are unacceptable to most German speakers.

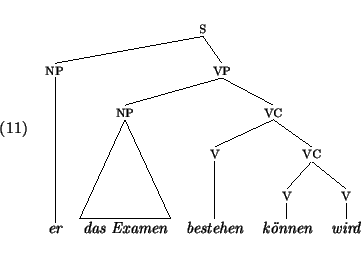

While the fact that auxiliaries and modal verbs are `argument-inheritance' verbs has been widely accepted, questions concerning the constituency of phrases headed by such argument-inheriting verbs have not been answered uniformly. In [8], for instance, it is argued that the verb cluster is right-branching instead of left-branching:

This analysis has the advantage that auxiliaries and modals can simply select for a lexical verb (a property it shares with the preliminary proposal presented in the previous section), instead of a verb cluster. Therefore, a uniform head-complement rule schema can be used and the feature NPCOMPS becomes superfluous. A problem for this kind of analysis is obviously that there is no easy way to account for auxiliary flip.

Of course, one can also give up the assumption that the VP is binary-branching. In [12], for instance, it is argued that instances of partial VP fronting (12) are best accounted for by making minimal assumptions about the internal structure of VP's.

For analyses that assume a correspondence between a fronted element and a trace in the remaining clause, such examples are problematic. Only an analysis that assigns multiple bracketings to das Buch lesen können can account for the two examples in (12). Such an analysis will lead to spurious ambiguity in examples without fronting. Nerbonne provides an alternative, traceless, account, in which a lexical complement extraction rule shifts an element from COMPS to SLASH. A special feature of this rule is that if an element on COMPS is required to be lexical (or [NPCOMPS -]), this constraint no longer holds for the element on SLASH. This essentially allows an argument-inheritance verb, that normally selects a lexical verb or verb cluster, to have an element on slash matching an arbitrary partial VP.6

Nerbonne emphasizes the fact that in his analysis fronting of partial VP's can no longer be used as an argument for assigning such phrases constituent-status in non-fronted positions as well. Consequently, there seems to be no reason why a verbal head could not combine with all its complements in one step. Although Nerbonne does not adress this issue in detail, he suggests that an account of auxiliary flip still necessitates the introduction of a verb cluster. In Nerbonne's analysis, the verb cluster is one of the arguments of the finite verb:

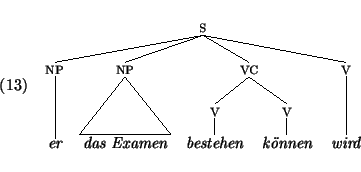

Baker [1] takes the analysis of Nerbonne one step further by assuming that the German VP is best assigned a `flat' structure, in which a verbal head combines with all its complements at once. Thus, our running example is assigned the following structure:

The analysis of Baker resembles the preliminary account presented in the previous section. The HEAD-COMPLEMENT schema presented in [1], for instance, allows a head of type word to combine with an arbitrary number of its complements, as in our rule (4). Furthermore, argument-inheritance verbs select for a lexical verbal complement. Baker accounts for auxiliary flip by assuming that auxiliaries which occur in flipped position no longer require a lexical verbal complement, but instead may select any partial VP (note that, as in our account, Baker does not exclude the formation of partial VP's altogether). As is admitted by Baker herself, this account overgenerates, as it not only accepts ordinary cases of auxiliary flip, but also the examples in (15), where example (15a) (which receives the derivation in (16)) is acceptable only to some speakers, and (15b) is completely ungrammatical.7

A peculiarity of Baker's analysis is that she assumes that in examples with standard (i.e. non-flipped) word order such as (14), there is a `flat' structure, whereas for examples of auxiliary flip such as wird lesen können she assumes that the double infinitive is a constituent. Since Baker does not use a feature NPCOMPS, her account must therefore also accept the examples in (15). If we want to exclude these (i.e. be able to describe dialects in which these examples are unacceptable) we must either reintroduce some system for distinguishing between verb clusters and other partial VP's, which would severely undermine the motivation for adopting a `flat' analysis, or else give up the assumption that `flipped' auxiliaries precede a single constituent. In section 5 we explore the latter option.