Debate on Representation (May 31)

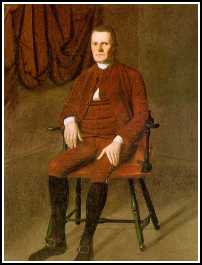

MR. SHERMAN

MR. SHERMAN - opposed the election by the people, insisting that it ought to be by the State legislatures. The people he

said, immediately should have as little to do as may be about the Government. They want information and are constantly

liable to be misled.

- MR. GERRY.

- The evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy. The people do not want virtue, but are the dupes

of pretended patriots. In Massachusetts it had been fully confirmed by experience that they are daily misled into the most

baneful measures and opinions by the false reports circulated by designing men, and which no one on the spot can refute. one

principal evil rises from the want of due provision for those employed in the administration of Government. It would seem to

be a maxim of democracy to starve the public servants. He mentioned the popular clamour in Massachusetts for the reduction

of salaries and the attack made on that of the Governor though secured by the spirit of the Constitution itseff. He had he said

been too republican heretofore: he was still however republican, but had been taught by experience the danger of the levolling

spirit.

- MR. MASON,

- argued strongly for an election of the larger branch by the people. It was to be the grand depository of the

democratic principle of the government. It was, so to speak, to be our House of Common~~It ought to know and sympathize

with every part of the community; and ought therefore to be taken not oniy from different parts of the whole republic, but

also fiom different districts of the larger members of it, which had in several instances particularly in Virginia different

interests and views arising from difference of produce, of habits etc., etc. He admitted that we had been too democratic but

was afraid we should incautiously run into the opposite extreme. We ought to attend to the rights of every class of the people.

He had often wondered at the indifference of the superior classes of society to this dictate of humanity and policy;

considering that however affluent their circumstances, or elevated their situations, might be, the course of a few years, not

only might but certaiuly would, distribute their posterity throughout the lowest classes of Society. Every selfish motive

therefore, every family attachment, ought to recommend such a system of policy as would provide no less carefully for the

rights and happiness of the lowest than of the highest orders of Citizens.

- MR. WILSON

- contended strenuously for drawing the most numerous branch of the legislature immediately from the people.

He was for raising the federal pyramid to a considerable altitude, and for that reason wished to give it as broad a basis as

possible. No government could long subsist without the confidence of the people. In a republican Government this confidence

was peculiarly essential. He also thought it wrong to increase the weight of the State Legislatures by making them the electors

of the National Legislature. All interference between the general and local governments should be obviated as much as

possible. On examination it would be found that the opposition of States to federal measures had proceded much more from

the officers of the States, than from the people at large.

- Mit. MADISON

- considered the popular election of one branch of the National Legislature as essential to every plan of free

Government. He observed that in some of the States one branch of the Legislature was composed of men already removed

from the people by an intervening body of electors. That if the first branch of the general legislature should be elected by the

State Legislatures, the second branch elected by the first, the Executive by the second together with the first; and other

appointments agaln made for subordinate purposes by the Executive, the people would be lost sight of altogether; and the

necessary sympathy between them and their rulers and officers, too little left. He was an advocate for the policy of refining

the popular appointments by successive filtrations, but thought it might be pushed too far. He wished the expedient to be

resorted to only in the appointment of the second branch of the Legislature, and in the Executive and judiciary branches of the

Government. He thought too that the great fabric to be raised would be more stable and durable, if it should rest on the solid

foundation of the people themselves, than if it should stand merely on the pillars of the Legislatures.

- MR. GERRY

- did not like the election by the people. The maxims taken from the British constitution were often fallacious

when applied to our situation which was extremely different. Experience be said had shown that the State legislatures drawn

irnmediately from the people did not always possess their confidence. He had no objection however to an election by the

people if it were so qualified that men of honor and character might not be unwilling to be joined in the appointments. He

seemed to think the people might nominate a certain number out of which the State Legislatures should be bound to choose.

- Documents >

- 1786-1800 >

- The Constitutional Convention debates and the Anti-Federalist

Papers >

- James Madison to George Washington (April 16, 1787)

- The Virginia Plan (May 29)

- Debate on Representation (May 31)

- Debate of Executive Power (June 1)

- Opposition to Executive Salaries (June 2)

- Opposition to a Unitary Executive (June 4)

- Electing Representatives (June 6)

- Debate on Method of Electing Senators (June 7)

- Debate on Veto of State Laws (June 8)

- The New Jersey Plan (June 15)

- Debate on The New Jersey Plan (June 16)

- Plan for National Government (June 18)

- Opposition to The New Jersey Plan (June 19)

- Debate on Federalism (June 21)

- Length of Term in Office for Senators (June 26)

- Debate on State Equality in the Senate (June 28-July 2)

- Majority Rule the Basic Republican Principle (July 5, 13, 14)

- Election and Term of Office of the National Executive (July 17, 19)

- The Judiciary, the Veto, and Separation of Powers (July 21)

- Appointment of Judges (July 21)

- Method of Ratification (July 23)

- Election of Executive (July 24, 25)

- First Draft of the Constitution (August 6)

- Qualifications of Suffrage (August 7, 10)

- Citizenship for Immigrants (August 9)

- Executive Veto Power (August 15)

- Slavery and Constitution (August 21, 22)

- Election and Powers of the president (Sept. 4, 5, 6)

- Opposition to the Constitution (Sept. 7, 10, 15)

- Signing the Constitution (Sept. 17)

- Speech of James Wilson (October 6, 1787)

- "John De Witt" Essay I, Oct.22, 1787

- "John De Witt" Essay II, Oct.27, 1787

- Speech of Patrick Henry (June 5, 1788)

- Amendments Proposed by the Massachusetts Convention,(Feb. 7, 1788)

- Amendments Proposed by the Virginia Convention, (June 27, 1788)

- Amendments to the Constitution (June 27, 1788)

- Amendments Proposed by The Rhode Island Convention (March 6, 1790)

- Speech of Patrick Henry (June 7, 1788)

MR. SHERMAN

MR. SHERMAN