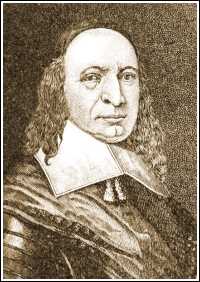

Peter Stuyvesant 1592-1672

Dutch Governor of the New Netherlands

Peter Stuyvesant (also known as Pietrus Stuyvesant), the son of a clergyman of Friesland, was born in the Netherlands in 1592. Stuyvesant served in the Dutch Army before receiving his appointment as director-general of New Netherland in 1646. He had served in the West Indies and was governor of the colony of Curacoa. He lost a leg during the unsuccessful assault on the Portuguese island of St. Martin, after which he returned to the Netherlands in 1644.

Two years later he was appointed director-general of New Netherlands, and took the oath of office on 28 July, 1646. He sailed to the new world and reached New Amsterdam on May 11, 1647. Soon after his inauguration on 27 May he organized a council and established a court of justice.

In deference to the popular will, he ordered a general election of eighteen delegates, from whom the governor and his council selected a board of nine, whose power was advisory and not legislative. A dictatorial leader, Stuyvesant was unpopular with the other settlers. However, during his eighteen year administration, the population grew from 2,000 to 8,000.

Immediately after his arrival he tried to reorganize the colony: he ordered the strict observance of Sunday rest and prohibited the sale of alcoholic beverages and weapons to the Indians. He also tried to increase state-income by heavier taxation on imports. To improve the quality of the colony he stimulated the colonists to build better houses and taverns, and established a market and an annual cattle-fair. He also showed interest in founding a public school.

Immediately after his arrival he tried to reorganize the colony: he ordered the strict observance of Sunday rest and prohibited the sale of alcoholic beverages and weapons to the Indians. He also tried to increase state-income by heavier taxation on imports. To improve the quality of the colony he stimulated the colonists to build better houses and taverns, and established a market and an annual cattle-fair. He also showed interest in founding a public school.

He tried to settel an old problem: the wuestion of the bounderies with other colonies. However, the government of the New England colony could not accept his terms. Because of the Dutch claim of jurisdiction in Connecticut he also became involved in a controversy with Governor of that colony.

The first two years of his administration were not successful. He had serious discussions with the patroons, who interfered with the company's trade and denied the authority of the governor, and he was also embroiled in contentions with the council, which sent a deputation to the Hague to report the condition of the colony to the states-general. This report was published as " Vertoogh van Nieuw Netherlandt" (The Hague, 1650). The states-general afterward commanded Stuyvesant to appear personally in Holland; but the order was not confirmed by the Amsterdam chamber, and Stuyvesant refused to obey, saying, " I shall do as I please."

In September, 1650, a meeting of the commissioners on boundaries took place in Hartford, whither Stuyvesant travelled in state. The line was arranged much to the dissatisfaction of the Dutch, who declared that "the governor had ceded away enough territory to found fifty colonies each fifty miles square." Stuyvesant grew haughty in his treatment of his opponents, and threatened to dissolve the council. A plan of municipal government was finally arranged in Holland, and the name of the new city of New Amsterdam--was officially announced on 2 February, 1653. Stuyvesant made a speech on this occasion, knowing that his authority would remain undiminished. The governor was now ordered to Holland again ; but the order was soon revoked on the declaration of war with England. Stuyvesant prepared against an attack by ordering his subjects to make a ditch from the North river to the East river, and to erect breastworks. In 1665 he sailed into the Delaware with a fleet of seven vessels and about 700 men and took possession of the colony of New Sweden, which he called New Amstel.

In his absence New Amsterdam was ravaged by Indians, but his return inspired confidence. Although he organized militia and fortified the town, he subdued the hostile savages chiefly through kind treatment. In 1653 a convention of two deputies from each village in New Netherlands had demanded reforms, and Stuyvesant commanded this assembly to disperse, saying" "We derive our authority from God and the company, not from a few ignorant subjects." The spirit of resistance nevertheless increased, and the encroachments of other colonies, with a depleted treasury, harassed the governor. In 1664 Charles II. ceded to his brother, the Duke of York, a large tract of land, including New Netherlands; and four English war vessels bearing 450 men, commanded by Captain Richard Nicholls, took possession of the harbor. On 30 August Sir George Cartwright bore to the governor a summons to surrender, promising life, estate, and liberty to all who would submit to the king's authority. Stuyvesant read the letter before the council, and, fearing the concurrence of the people, tore it into pieces. On his appearance, the people who had assembled around the city-hall greeted him with shouts of "The letter ! the letter ! " and, returning to the council-chamber, he gathered up the fragments, which he gave to the burgomasters to do with the order as they pleased. He sent a defiant answer to Nicholls, and ordered the troops to prepare for an attack, but yielded to a petition of the citizens not to shed innocent blood, and signed a treaty at his Bouwerie house on 9 September, 1664. The burgomasters proclaimed Nicholls governor, and the town was called New York.

In 1665 Stuyvesant went to Holland to report, and labored to secure from the king the satisfaction of the sixth article in the treaty with Nicholls, which granted free trade. During his administration commerce had increased greatly, the colony obtaining the privilege of trading with Brazil in 1648, with Africa for slaves in 1652, and with other foreign ports in 1659. Stuyvesant endeavored unsuccessfully to introduce a specie currency and to establish a mint in New Amsterdam. He was a thorough conservative in church as well as state, and intolerant of any approach to religious freedom. He refused to grant, a meeting-house to the Lutherans, who were growing numerous, drove their minister from the colony, and frequently punished religious offenders by fines and imprisonment.

On his return from Holland after the surrender, he spent the remainder of his life on his farm of sixty-two acres outside the city, called the Great Bouwerie, beyond which stretched woods and swamps to the little village of Haarlem (Harlem). The house, a stately specimen of Dutch architecture, was erected at a cost of 6,400 guilders, and stood near what is now Eighth street. Its gardens and lawn were tilled by about fifty negro slaves. A pear-tree which he brought from Holland in 1647 remained at the corner of Thirteenth street and Third avenue until 1867, bearing fruit almost to the last. The house was destroyed by fire in 1777. He also built an executive mansion of hewn stone called Whitehall, which stood on the street that now bears that name.

Stuyvesant continued to live on his estate on Manhattan Island until his death in 1672.