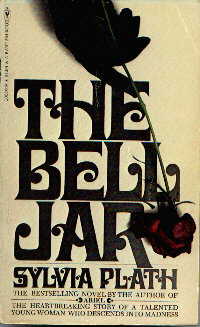

Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath lived an outwardly exemplary life, attending

Smith College on scholarship, graduating first in her class, and

winning a Fulbright grant to Cambridge University in England.

There she met her charismatic husband-to-be, poet Ted Hughes,

with whom she had two children and settled in a country house in

England. Beneath the fairy-tale success festered unresolved

psychological problems evoked in her highly readable novel The

Bell Jar (1963). Some of these problems were personal, while

others arose from repressive 1950s attitudes toward women. Among

these were the beliefs -- shared by most women themselves -- that

women should not show anger or ambitiously pursue a career, and

instead find fulfillment in tending their husbands and children.

Successful women like Plath lived a contradiction.

Sylvia Plath lived an outwardly exemplary life, attending

Smith College on scholarship, graduating first in her class, and

winning a Fulbright grant to Cambridge University in England.

There she met her charismatic husband-to-be, poet Ted Hughes,

with whom she had two children and settled in a country house in

England. Beneath the fairy-tale success festered unresolved

psychological problems evoked in her highly readable novel The

Bell Jar (1963). Some of these problems were personal, while

others arose from repressive 1950s attitudes toward women. Among

these were the beliefs -- shared by most women themselves -- that

women should not show anger or ambitiously pursue a career, and

instead find fulfillment in tending their husbands and children.

Successful women like Plath lived a contradiction.

Plath's storybook life crumbled when she and Hughes separated and she cared for the young children in a London apartment during a winter of extreme cold. Ill, isolated, and in despair, Plath worked against the clock to produce a series of stunning poems before she committed suicide by gassing herself in her kitchen. These poems were collected in the volume Ariel (1965), two years after her death. Robert Lowell, who wrote the introduction, noted her poetry's rapid development from the time she and Anne Sexton had attended his poetry classes in 1958. Plath's early poetry is well-crafted and traditional, but her late poems exhibit a desperate bravura and proto-feminist cry of anguish. In "The Applicant" (1966), Plath exposes the emptiness in the current role of wife (who is reduced to an inanimate "it"):

It works, there is nothing wrong with it.

It can sew, it can cook.

It can talk, talk, talk.

You have a hole, it's a poultice.

You have an eye, it's an image.

My boy, it's your last resort.

Will you marry it, marry it, marry it.

Plath dares to use a nursery rhyme language, a brutal directness. She has a knack for using bold images from popular culture. Of a baby she writes, "Love set you going like a fat gold watch." In "Daddy," she imagines her father as the Dracula of cinema: "There's a stake in your fat black heart / And the villagers never liked you."